The Norwegian architect Espen Øino, photo ©Guillaume Plisson

The next frontier in yachting? Espen Øino is thinking nuclear

Presented at the Monaco Yacht Show in collaboration with Emerald Nuclear and PTT Nuclear Energy Systems, Øino’s Modular Nuclear Reactor Concept explores how next-generation nuclear technologies could redefine performance, autonomy, and sustainability in yachting.

Norwegian by birth and Monegasque by adoption, Espen Øino is today one of the most influential yacht designers in the world. For over thirty years, his name has been associated with some of the most iconic projects in the industry, from the pioneering MY Eco – later renamed Zeus – to the celebrated 126-metre MY Octopus.

Born in Oslo and raised between skiing and sailing along Norway’s rugged coastline, Øino studied naval and offshore engineering at the University of Glasgow, specialising in floating structures, stability, and hydrodynamics. After a formative experience at Martin Francis’s design studio, where he co-signed his first motor yacht, he founded Espen Øino International in 1994 — now a Monaco-based design atelier with a team of more than thirty professionals.

Below is our interview about the Nuclear Energy Systems project.

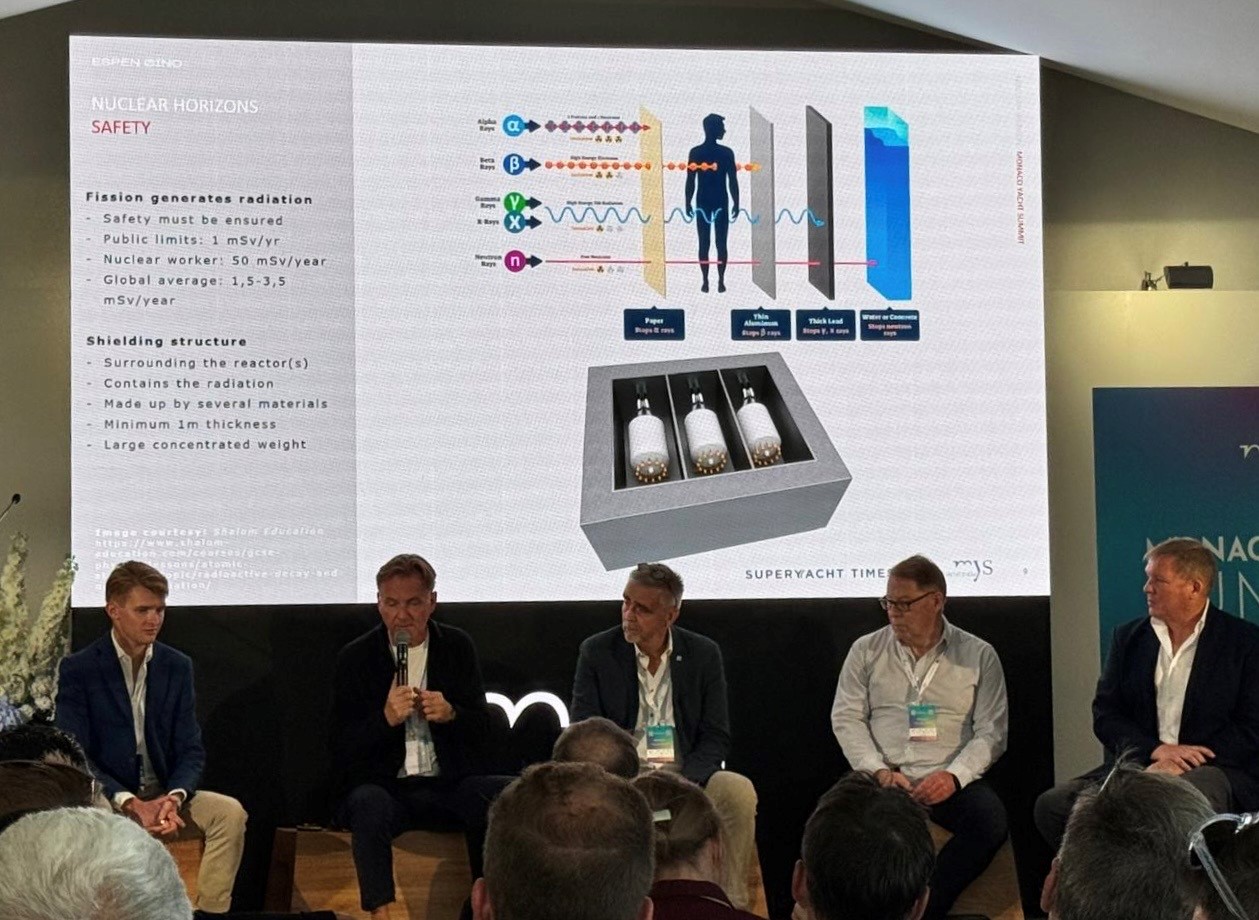

Balancing Safety and Innovation

PressMare - Given the strict regulatory, safety, and environmental concerns around nuclear propulsion, how would you balance innovation with risk—both for the owner/user and for broader reputational or regulatory exposure for the yacht designer/shipyard?

Espen Øino - The balance lies in the technology itself. What we’re seeing today is a completely new generation of modular nuclear reactors—small, intrinsically safe, and engineered specifically for mobile applications. Unlike the legacy systems used in Chernobyl or Fukushima, these reactors use Triso fuel, which is encapsulated in pyrolytic carbon and silicon carbide, making it virtually impossible to melt. That alone mitigates the risk of thermal runaway or radiation leaks.

From a regulatory and reputational standpoint, the key is transparency and education. Public perception is evolving, especially as energy demands from sectors like AI and data centers skyrocket. Countries that once shut down nuclear programs, like Germany, are reopening the conversation. For yacht designers and shipyards, the challenge is to communicate clearly: the owner doesn’t operate the reactor—they buy power. The reactor is installed, maintained, and operated by a third party. That legal separation is crucial for liability and public trust.

We’re also seeing strong engagement from classification societies and flag states. They’re working fast, collaboratively, and with purpose. The emergency planning zones for these new reactors are contained within the ship’s dimensions, meaning they don’t affect port infrastructure or territorial waters. That’s a game-changer for regulatory acceptance.

Integration with Owner’s Vision and Usage Profile

PM - When owners commission yachts, they often have strong ideas about usage—Mediterranean cruising, expedition, speed, comfort, services. How would nuclear propulsion fit into different usage profiles? In what scenarios do you think it makes the most sense, and when might it be overkill or impractical?

EØ - Nuclear propulsion makes the most sense for vessels with high operational profiles—long-range expedition yachts, icebreakers, or commercial ships that are underway 90% of the time. These vessels benefit from consistent, high-output power generation. A 5 MW modular reactor produces electricity 24/7, 365 days a year. That’s ideal for ships that need to be self-sufficient and operational in remote areas.

For typical superyachts, which are stationary or at anchor 80–85% of the time, nuclear might be overkill. The power output exceeds what’s needed for leisure cruising. However, for visionary owners—those who want to push boundaries, explore polar regions, or operate with zero emissions—it’s a compelling proposition.

We’ve already seen this mindset with hydrogen installations, like on the recent Fedship “Breakthrough,” and with innovations like the Dynarig on Maltese Falcon. These owners are willing to invest in first-of-kind systems. Nuclear propulsion could be the next frontier for them.

Regulation and Classification Hurdles

PM - What do you see as the main regulatory or classification challenges that must be addressed before nuclear propulsion can become viable in the superyacht sector—both in terms of international maritime law and classification societies? And what steps would you consider most important to move those conversations forward?

EØ - The biggest hurdle is harmonizing international maritime law with emerging nuclear technologies. Today, there are around 200 nuclear-powered vessels, mostly military. Civilian applications are rare, and many countries still restrict nuclear ships from entering territorial waters due to outdated emergency planning assumptions.

The new modular reactors change that. Their emergency zones are internal, they require minimal crew intervention, and they’re designed to be swapped like gas bottles—contained, shielded, and managed by the provider. That simplifies the legal framework.

Classification societies and flag states are already forming working groups. The most important step is to demonstrate real-world applications. That’s why we’re working with Emerald Nuclear in Seattle and their Norwegian subsidiary to build a demonstrator reactor by 2029, installed on a barge near the Technical University and the city of Aalto. The first shipboard installation is planned for 2031 on a platform supply vessel.

Once regulators see these systems in action—safe, efficient, and self-contained—the conversation will shift from theoretical to practical. Insurance companies are already engaging. That’s a strong signal.

Technological and Design Implications

PM - From a design and naval architecture perspective, what are the key technological obstacles with nuclear propulsion? How might these affect yacht layout, weight distribution, habitable spaces, costs, and lifecycle management?

EØ - The main design challenge is weight concentration. Traditional fuel tanks distribute weight evenly along the hull. A nuclear reactor, even modular, is a high-density unit—typically 400–450 tons of shielding alone. That weight needs to be placed centrally to avoid structural imbalance.

We addressed this in our concept for a 120-meter yacht, where two 5 MW reactors are housed in 20-foot containers below the tender garage. This allows for easy removal and replacement without cutting into the hull—unlike diesel generators that require side access for servicing.

Lifecycle management is also simplified. The reactor is sealed, requires no crew intervention, and is reviewed every five years. One fuel load can last 15–25 years, depending on usage. Spent fuel remains inside the reactor and is recycled by the provider. That’s a major advantage over conventional systems.

Habitable spaces aren’t compromised. The shielding ensures no radiation exposure, and the power conversion system—using supercritical CO₂ or nitrogen—is entirely separate, with no radiation transfer. Efficiency reaches up to 45%, far better than traditional steam turbines.

Market Demand & Owner Acceptability

PM - What is your sense of owner demand for truly zero-emission or radically low-emission propulsion systems? Do you think there are owners who would accept nuclear propulsion on yachts not only from a performance but also from a perception standpoint? What communication challenges do you foresee?

EØ - Owner demand is growing, especially among those who understand the limitations of current alternatives. Green hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia are energy-intensive to produce. You need more power to create them than you get back. That’s not sustainable at scale.

Nuclear offers unmatched energy density. It’s the only realistic path to net zero for shipping, which accounts for 3% of global emissions. Owners who value performance, autonomy, and sustainability will see the appeal—especially as public perception shifts.

Communication is key. We must demystify nuclear. It’s not about radiation or risk—it’s about electrification. The reactor is a heat source. The propulsion is electric. That’s the same principle behind EVs, which have revolutionized transport in places like Norway, where 95% of new car sales are electric.

Insurance, port access, and public trust will follow once the first demonstrators are online. We’re already seeing financiers and insurers who were skeptical two years ago now actively pursuing partnerships. The tide is turning.

PM - Thank you, Espen Øino. Your insights are not only technically rich but also visionary. This conversation will certainly help our readers understand the real potential of nuclear propulsion in yachting and beyond.

EØ - Thank you. It’s an exciting time. The future of marine mobility is electric—and nuclear is the enabler.

Filippo Ceragioli

©PressMare - All rights reserved