There are a few key differences between Asymmetric spinnakers designed for offshore racing and those that are optimised for windwardleeward races inshore.

A-sail design principles, carefully explained by UK Sailmakers

To explain the thinking that goes into designing asymmetrical spinnakers, we interviewed three sail designers from UK Sailmakers: lead designer Pat Considine, UK Sailmakers Chicago; Geoff Bishop, UK Sailmakers Fremantle, and Stuart Dahlgren, UK Sailmakers Northwest - Sidney, BC. Their thoughts on spinnaker design fell into two buckets.

1. The boat itself

Type of boat - high-performance, displacement, one-design.

Exact measurements - pin-to-pin halyard length, sheeting position, etc.

2. The type of sailing to be done

IRC, ORC, offshore, coastal, onedesign, professional vs. Corinthian.

Key data points

When designing an asymmetrical spinnaker, a designer will focus on three primary data points:

1. The point-to-point distance between where the spinnaker will be tacked (on a sprit or a lowered pole) and the max height for the halyard.

2. The mid-girth (SMG) luff to leech measurement, expressed as a percentage of the foot length.

3. The trim position for the clew in terms of height off the deck and where the sheet will lead.

Pat Considine explains: ‘A symmetrical spinnaker is probably the easiest sail to design. It has no twist and both sides are the same. An asymmetrical spinnaker on the other hand is challenging to design because the luff is free flying, there’s twist in the leech and there are many other things to consider.’

Our sailmaker panel agreed that once the boat characteristics and racing plans are known, additional pre-design considerations include:

The performance characteristics of the boat such as polars, reaching/running angles and so on

The other spinnakers in the inventory: can this new sail have a narrow range or should it be all-purpose?

Rating system to be sailed, optimisation for IRC, ORC, etc

Budget: Yes, there is less expensive nylon and more expensive nylon. With spinnakers you get what you pay for

The skill of the owner: experienced sailors (helm and trimmers) will not need as forgiving a spinnaker as less experienced sailors.

Geoff Bishop adds: ‘Once you get a good sail design and you know the boat’s measurements, you pretty much stick with it. That said, the critical thing for me is getting the luff length and the mid-girth ratio right.

‘Start with the straight-line measurement from the tack to the max hoist position (straight line), the tack point to the sheeting position, plus the sheeting position to the max hoist position. It’s critical to get those measurements right because every percent of difference in mid-girth in relation to the foot and luff length changes performance and ratings.’

A running sail could have a 105% mid-girth (SMG) of the foot length (SF) and a luff length longer than the straight-line measurement. Conversely, a reaching sail will have a smaller SMG in relation to the foot length as well as a shorter luff.

Luff length

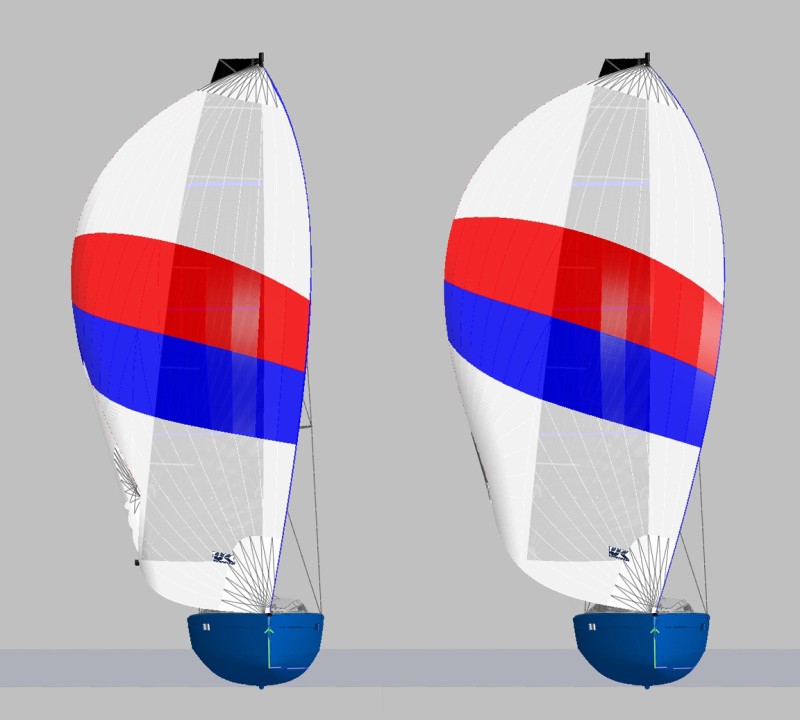

The luff length helps to determine the projection of the sail. For windward/leeward racing, mostly in displacement boats, the goal is to soak for VMG. For that you want a luff that is longer than the pin-to-pin measurement; this creates positive luff curve allowing the sail to project to windward further so you can sail deeper on those shorter round-thebuoys races. If a spinnaker luff keeps collapsing when properly trimmed, the entry is probably too flat. One of your tools is the tackline: if it has been eased to allow more projection, pull it back down to help round the entry, making it easier to trim.

To design a good A-sail, the entry must be deep enough to support the luff round and allow the luff to curl without collapsing. Consider a heavy J1 jib. To sail that J1 upwind in a groove, you need curvature in the luff so the telltales work. Reachers (A1, A3, A5) will be designed flatter and straighter in the aft section to avoid the sail getting overpowered too quickly. Runners (A2, A4) tend to have deeper, rounder aft sections.

For running asyms, the luff length can range from 105-112% of the pin-to-pin measurement. 112% would be for a boat like a J/120 where projection is important. The longer luff helps to increase projection when sailing at the deeper angles.

Tweakers are another tool that can be used to improve your sail’s performance. As the sheet is eased the active tweaker should be tensioned, effectively moving the sheet lead forward, this controls twist and allows the designed depth to be maintained, so that the head doesn’t flip open as the sail is eased.

All these contributing factors that make displacement boats’ VMG quick downwind are your enemies when sailing a performance boat offshore in waves. Unlike displacement boats, performance boats generate tremendous amounts of apparent wind. With the apparent wind angle rarely aft of 110 degrees, the helmsperson will drive down to surf waves then turn up to regain speed and height. Displacement boats also may surf down a wave moving the apparent wind forward but when they put the bow up to dig out of the trough, they won’t respond as quickly. Also, the apparent wind shifts relatively more than on a performance boat.

Offshore and coastal running sails generally have the same depth, but what differs would be the luff length defining the luff round, and the overall projection of the luff. This is achieved by designing the sail’s optimal flying shape and then engineering the panel layout to handle the loads and maintain stability.

Sailing in waves you “drive” the boat more aggressively moving the apparent wind more dynamically. If conditions allow the boat to be stable, it’s great to have a super long luff; but when the boat starts to move around under the sail, oscillation increases as do the chances of collapse or wrapping the sail around the forestay. There is also the physical limitation on how long the crew can keep up aggressively trimming the sheet in a distance race.

Because of the relatively smaller shifts in apparent wind angle in performance boats, their offshore spinnakers are cut flatter with a tighter luff. This design will be more resistant to collapsing from a serpentine steering pattern through waves. By adjusting the tackline you have more range with this sail.

Mid-girth measurement (SMG)

A big difference between one-design or coastal and offshore spinnakers is the mid-girth measurement (SMG). Offshore, where you typically sail at higher wind angles, your asym’s SMG is likely to be narrower depending on whether it is an A1, A3 or A5. Coastal or one-design spinnakers, used more for VMG running (A2 and A4) will have a wider SMG, as you’re looking to soak deeper. This wider SMG design will allow the sail to rotate out in front and to windward further in the VMG soak mode.

Sheeting position/leech length

The leech in an offshore asymmetric isn’t much different than a coastal or one-design sail, yet it’s still critical to get the clew height and sheeting angle right. The amount of fullness in the back end comes down to the type of spinnaker it is. Reachers are flatter in their aft sections so that you don’t get overpowered as quickly. Runners’ leech sections tend to be rounder, generating more power.

Pat Considine continues: ‘With our computer design software it’s very easy for us to change the depth of the sail but it’s important that you understand the corner-to-corner loads. Someone may be looking to save time and money by designing an asym with fewer panels but that’s no good because of the bias loads going across the panels. Designing a sail to have more panels that are narrower will result in a structurally stronger sail. We orient panels so the warp and fill yarns reflect the load paths of the sail. We also specify heavier fabric with narrower panels in luff, where most of the load is.’

Tweaking the leech shape

As the true wind angles being sailed change, you will want to control the leech shape and sheeting angle of the sail. Attaching a tweaker to the sheet allows you to raise or lower the sheeting angle and optimize the twist and exit angle of the sail.

Geoff Bishop notes: ‘With our running sails, if you’re in eight knots with a 150-degree target angle, we’d put on a little tweaker. But if we had to head up to 140 degrees to gain speed, we’d release the tweaker. We constantly play the tweaker up and down to optimise leech shape and control twist.’

Overtightening the tweaker will close the leech and prevent it from exhausting properly. To sail deeper angles, ease the sheet so the sail rotates forward and tension the tweaker to control twist.

Summary

Taking the time to understand the boat and the manner of sailing it will do is critical to designing and building an asymmetrical spinnaker that will help you win races. After that, it’s up to you to properly adjust and set the spinnaker so it will match the design’s optimal flying shape.

If you are looking for a new asymmetrical spinnaker for your boat, don’t just take what you’re given. Ask questions about the key measurement points of the sail, understand the performance differences of various options and then practice to sail it effectively. If you do this, you’ll be able to sail with confidence.