Aluminium on board: a solution to reduce a boat’s environmental impact

In the following technical contribution, Eng. Carlo Tonarelli, founder of Phiequipe, addresses the issue of sustainability in yacht construction starting from a concrete analysis of the product life cycle. Through a case study applied to the Levriero models, Tonarelli explains how the combined use of fiberglass and aluminium allows for a measurable reduction in environmental impact, without compromising aesthetics, functionality, or build quality.

A rational, engineering-driven approach, fully consistent with Phiequipe’s philosophy, whose boats—also appreciated by the market as tenders for large yachts—are the result of careful, conscious design choices with a long-term perspective.

Caption Carlo Tonarelli

We are living in a period of major transition, not only from an ecological standpoint: the world, taken as a whole, is no longer the same as it was five years ago, and it is unlikely to be the same five years from now.

In times like these, new paths are explored, experimentation takes place, mistakes are made, ambitious goals are set, and a balance is sought between economics, politics, society, and the environment. Environmental awareness, in particular, requires not only decisions, but also reflection, allowing for a critical analysis of what is happening around us.

Each of us, individually and as part of a broader system, can do our part, whether small or large. Large companies invest in research, study and test new technologies to reduce pollution, develop new production techniques, adopt materials derived from recycling, and seek production synergies. Individuals can rationalize waste and emissions by acting on daily habits and behaviours: turning off lights, lowering heating by a couple of degrees, using natural ventilation, car sharing, reducing plastic consumption, paying attention to recycling, and so on.

The yachting industry follows the same trend: leading shipyards explore new and sometimes bold solutions, even knowing that they may not be the right ones, as they themselves often admit. They do so out of a desire and ambition to be pioneers. They can afford to, and it is positive that they do: it benefits everyone.

Smaller companies are in a position similar to that of individuals mentioned earlier: despite limited resources, they can still do something. And they must do so.

We are currently in a transition phase in which certain high-level political decisions have a significant impact on technological development in some sectors and may ultimately prove not entirely correct.

However, under equal boundary conditions, it is possible to adopt solutions and make choices that, without major investments, allow emissions to be reduced and leave future generations not necessarily a better world, but at least one that is easier to recycle.

The first step is to think and clearly define the problem. Phiequipe is a company whose core business is technical consultancy and the production of high-end small craft, and is therefore naturally accustomed to thinking in analytical terms. The real environmental impact of a product is not concentrated in its use phase, but must be sought in its production and disposal phases.

When talking about boats, given the limited number of operating hours per year, the CO₂ emissions generated while navigating represent a very small percentage of the emissions produced over the entire life cycle (Life Cycle Assessment).

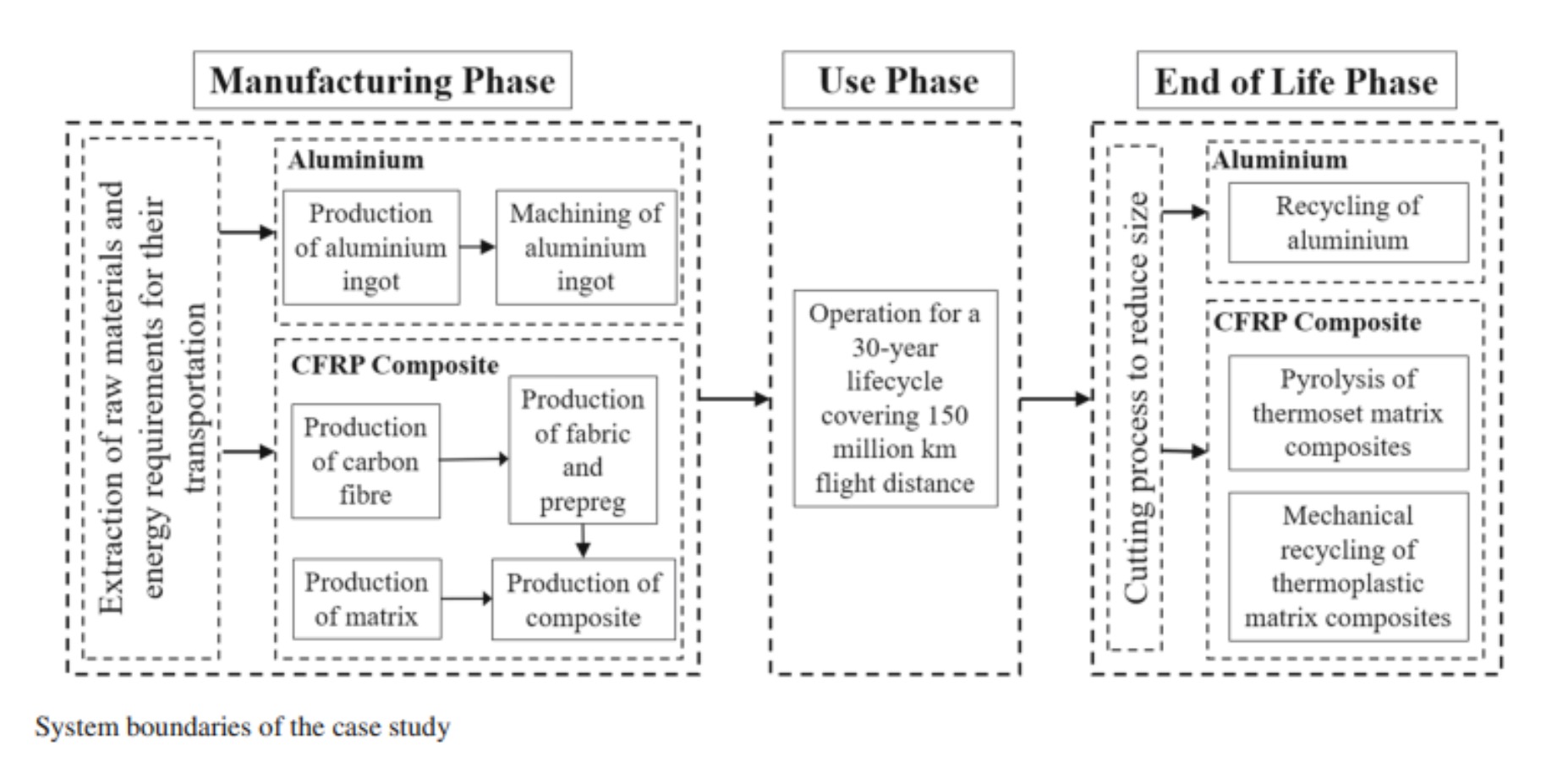

It is therefore necessary to raise the level of analysis and consider what happens before and after the boat is used: as if we placed a camera not on a close-up of the boat, but on the entire field that precedes and follows it, as shown in Figure 01.

Phiequipe proposes fuel-efficient engines to its owners, recommends power ratings appropriate to the boat’s weight and type, promotes conscious use of its Levriero models, and selects design speeds that are enjoyable but not excessive—all factors that ultimately translate into reduced emissions.

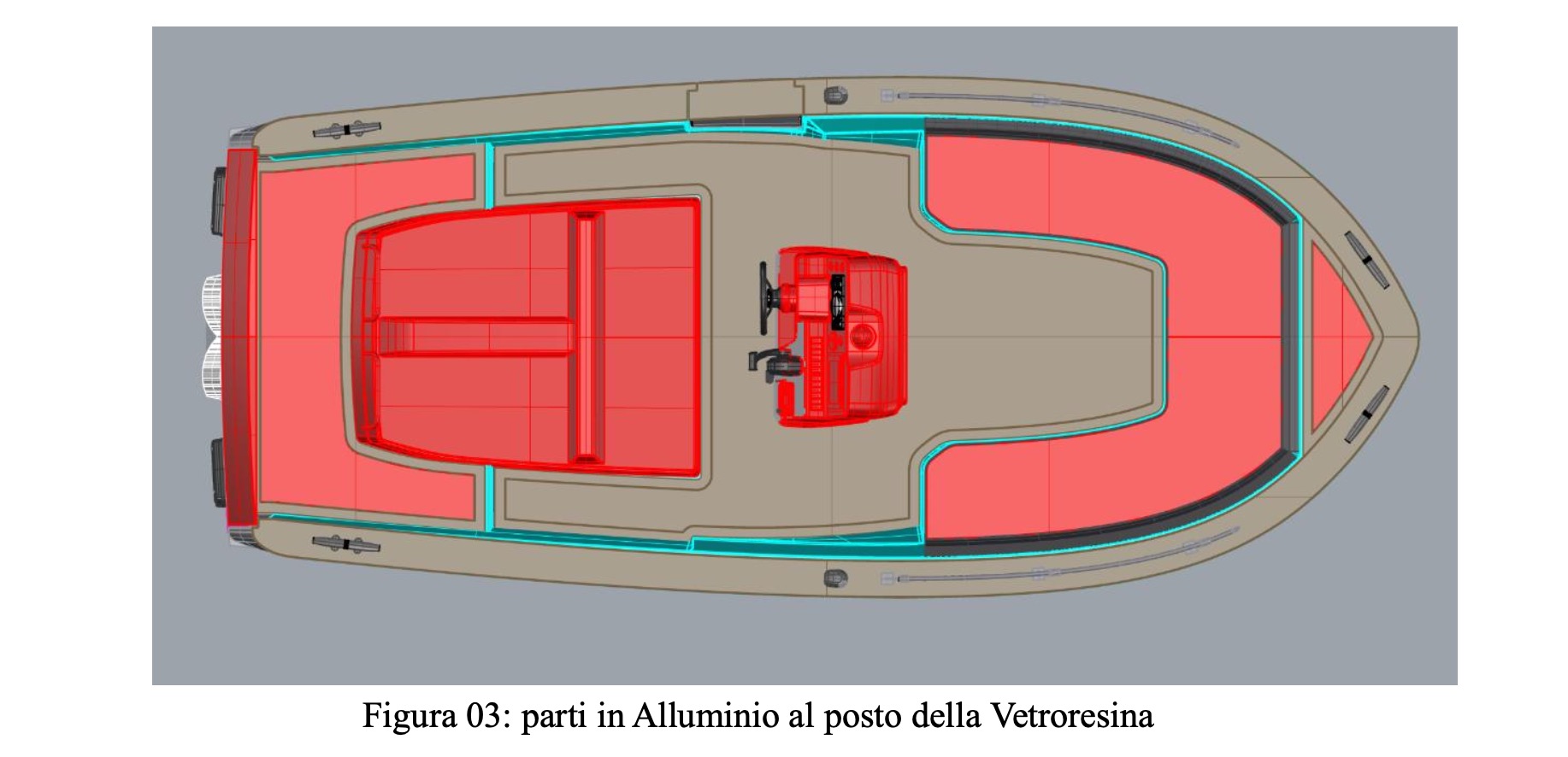

We can analyse a case study carried out by Phiequipe on its own boats, involving the partial use of aluminium on board a Levriero model, while keeping the rest of the boat unchanged in terms of materials.

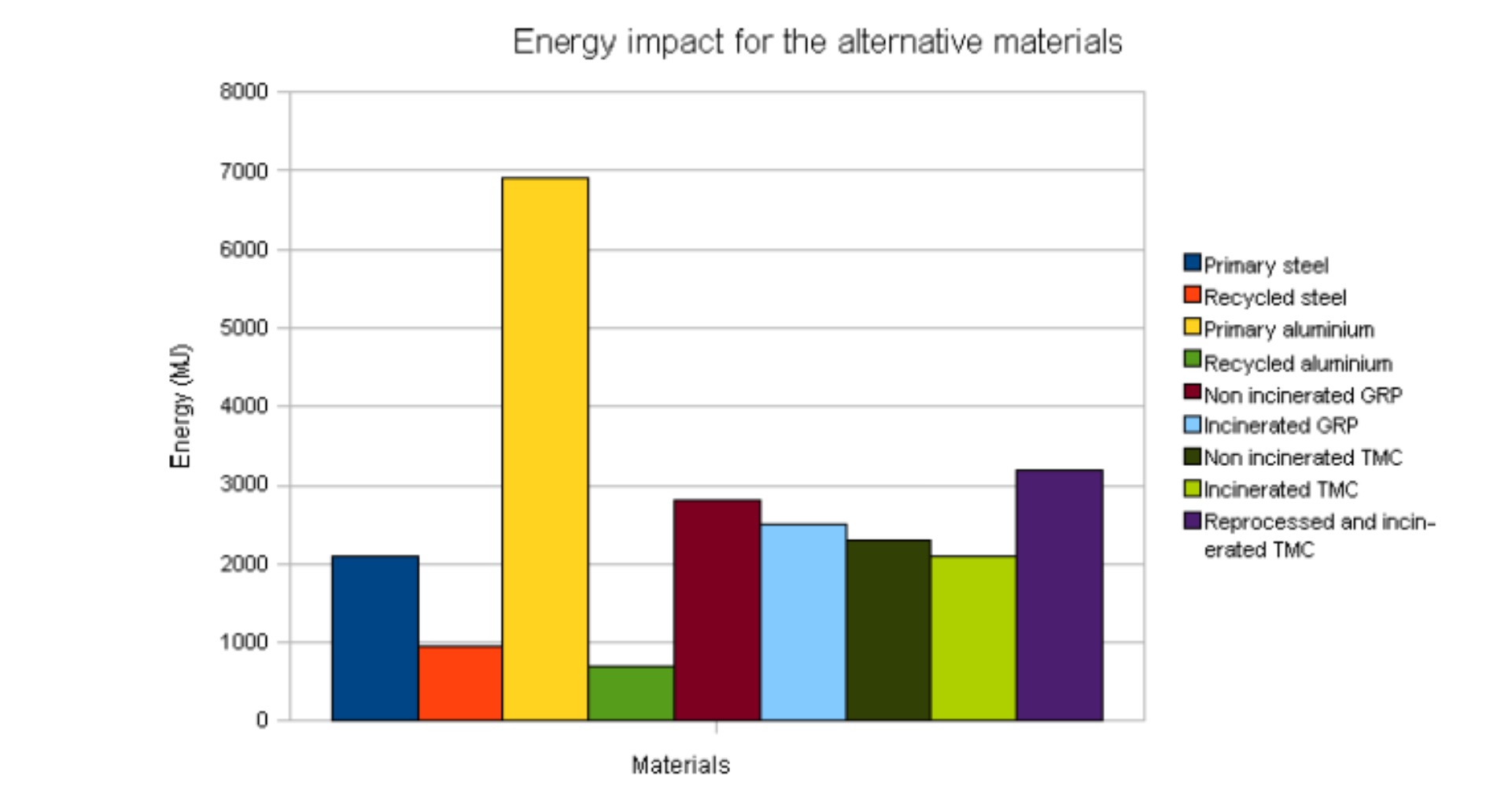

Aluminium is one of the most easily recyclable materials, and producing second-generation aluminium requires 95% less energy than producing primary aluminium. Recycling aluminium is therefore not only simple, but also highly efficient.

To give an idea, recycling 12 aluminium cans saves enough energy to power a conventional car for approximately 5 km. Some preliminary considerations underpin the case study carried out by Phiequipe on one of its models, the Levriero 21:

• Levriero owners do not accept a fully aluminium boat, which in any case requires great care to prevent galvanic corrosion phenomena;

• The use of aluminium components is introduced at the design stage, limited to non-structural parts that are easily repairable or removable, such as detachable elements with designs avoiding double-curvature surfaces or entirely flat parts;

• The boat remains primarily built in fiberglass, with selected aluminium components.

• No structural discontinuities are introduced, and galvanic corrosion is easy to prevent;

• No galvanic corrosion is introduced to the hull;

• The use of aluminium must not impact the boat’s aesthetics, and no visible welds are desired;

• A service life of 30 years is assumed, with annual antifouling maintenance;

• Emissions during the use phase are disregarded, as they are identical in both configurations (all fiberglass vs. partial fiberglass + aluminium) and do not affect the difference between the two solutions.

Under these assumptions, a 13% reduction in CO₂ emissions over the entire Life Cycle Assessment is achieved. Even if second-generation fiberglass were used for the same 17 m² surface, a reduction of 6% would still be obtained.

The key reflection, however, is that beyond the reduction in LCA emissions, a product is introduced into the market that, in 30 years’ time, will be far easier to recycle.

This is one of the most relevant aspects, which is sometimes overlooked: polluting less does not only mean emitting less CO₂ in the short term by producing items with low emissions during use.

It also means starting to design and manufacture products by considering, from the initial design inputs, how and with which materials they are industrialized, with the aim of reducing emissions, as well as how they will be disposed of and how easily future generations will be able to recycle them.

©PressMare - All rights reserved